PowerPoint and the dreaded listicle (familiar from clickbait K-holes like Thought Catalog) have given the list a bad name. But lists can be highly effective, turning prose into poetry by giving a passage an almost liturgical cadence or rummaging in the overstuffed drawers of your, or your character’s, mind.

Old Testament authors work the list like a musical riff, most memorably in Ecclesiastes (“A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted…”). To be sure, what gives this chapter its lyrical quality is the author’s use of anaphora (“repetition of a word or expression at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, sentences, or verses especially for rhetorical or poetic effect”), but most readers aren’t rhetoricians; they focus not so much on the repeated phrase (“a time”) as on the rhythm it taps out. It makes poetic music, so much so that Pete Seeger lifted its verses for his song “A Time for Everything” (you know it, if you know it at all, as “Turn! Turn! Turn!” by The Byrds).

Walt Whitman is the unchallenged master of “catalogue verse,” at least in the American mind. (In the ‘50s and ‘60s, Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg exalted him as a Transcendentalist in hogwashers—a big-hearted bard for the Coney Island masses, rhapsodizing about our collective self in a “barbaric yawp.”) By turns ecstatic, erotic, pensive, poignant, sensual, and melancholy, “Song of Myself,” his free-verse hymn to the American Me (but also the human condition), is a catalogue of catalogues. Its lists inventory stray thoughts and fleeting sensations of a changeable, “untranslatable” self:

The blab of the pave, tires of carts, sluff of boot-soles, talk of the promenaders,

The heavy omnibus, the driver with his interrogating thumb, the clank of the shod horses on the granite floor,

The snow-sleighs, clinking, shouted jokes, pelts of snow-balls,

The hurrahs for popular favorites, the fury of rous’d mobs,

The flap of the curtain’d litter, a sick man inside borne to the hospital,

The meeting of enemies, the sudden oath, the blows and fall,

The excited crowd, the policeman with his star quickly working his passage to the centre of the crowd,

The impassive stones that receive and return so many echoes…

…I mind them or the show or resonance of them—I come and I depart.

Here, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s transparent eyeball, the self-transcendent consciousness in egoless communion with the world of the senses, meets the steadycam. Whitman’s list of things seen and heard immerses us in the moment, riding the eddies of his stream of consciousness. This is list as montage of qualia, channeling the sensory life of another self.

Through rhythm, and by dint of their parallelism, long lists, especially epic catalogues like Whitman’s, take on a mesmeric quality, piling image on image, doing what the maximalist aesthetic does best: induce intellectual and sensory vertigo. Or they can just signal plenitude, or infinitude—the ecstasy of excess.

The catalog is an ancient device, used in epic poetry and, as noted, the Bible to evoke a stately, liturgical feel conducive to reverence or rumination; elegy or reverie. In modern usage, by contrast, the list often uses the seemingly random detritus of a character’s possessions to trace the chalk outline of a psyche: we are what we own. Think of Twain’s inventory of what’s in Tom Sawyer’s pockets:

He had…twelve marbles, part of a Jew’s harp, a piece of blue bottle-glass to look through, a spool cannon, a key that wouldn’t unlock anything, a fragment of chalk, a glass stopper of a decanter, a tin soldier, a couple of tadpoles, six firecrackers, a kitten with only one eye, a brass doorknob, a dog collar—but no dog—the handle of a knife, four pieces of orange peel, and a dilapidated old window sash.

There’s a whole cabinet of curiosities, here, one that reveals much about Tom’s inner life. The first thing we notice is that his imagination hasn’t undergone the obedience training that puts its free play on a choke chain. What’s trash to an adult is treasure to a boy, transformed into something rich and strange by Tom’s ingenious ability to find quirky uses for rubbish: a bit of bottle-glass turns the world blue when you look through it; a discarded spool can be reborn as a toy cannon. Alternatively, he puts lost or tossed-off things to poetic use, delighting in them purely for themselves, indifferent to the practical purposes they once served. Twain was in his forties when he wrote the novel, but he still has ready access to the boy he was, and to the alchemy of the childish imagination, which transmutes “a dog collar—but no dog”; “the handle of a knife”—but no knife; “four pieces of orange peel”—but no orange; and “a dilapidated old window sash”—but no window—into talismans for conjuring up an imaginary pet dog or a swashbuckler’s sword or a juicy orange or pirate’s sash. “A key that wouldn’t unlock anything” can be a passkey to the mysteries of the adult world. The “glass stopper of a decanter,” unable to do its job, can still be a source of aesthetic pleasure for those with eyes to see. Twain’s inventory of Tom’s precious rubbish makes it clear that he has just such an eye, and just such a nimble, imaginative wit.

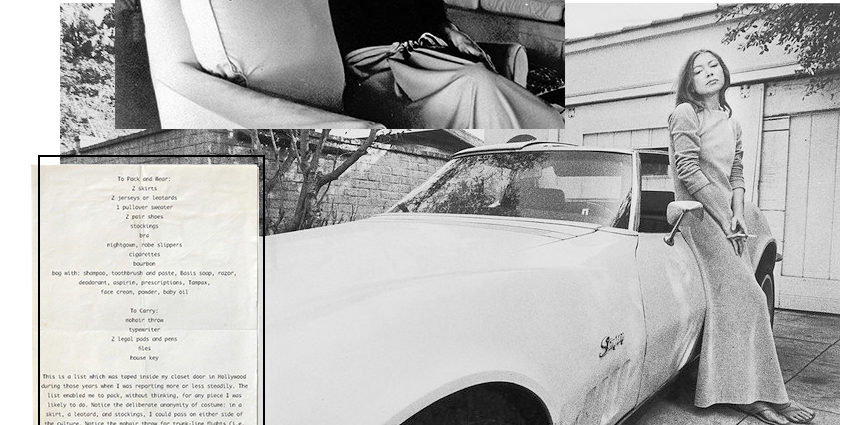

On an angstier, more neurotic note, Joan Didion’s famous packing list in The White Album is a functional MRI of her need for order in a turbulent time, the 1960’s:

TO PACK AND WEAR:

2 skirts

2 jerseys or leotards

1 pullover sweater

2 pair shoes

stockings

bra

nightgown, robe, slippers

cigarettes

bourbon

bag with: shampoo

toothbrush and paste

Basis soap, razor

deodorant

aspirin

prescriptions

Tampax

face cream

powder

baby oil

TO CARRY:

mohair throw

typewriter

2 legal pads and pens

files

house key

Reading the subtext for us, Didion deconstructs herself: “This is a list which was taped inside my closet door in Hollywood during those years when I was reporting more or less steadily. The list enabled me to pack, without thinking, for any piece I was likely to do. Notice the deliberate anonymity of costume: in a skirt, a leotard, and stockings, I could pass on either side of the culture. Notice the mohair throw for trunk-line flights (i.e. no blankets) and for the motel room in which the air conditioning could not be turned off. Notice the bourbon for the same motel room. Notice the typewriter for the airport, coming home: the idea was to turn in the Hertz car, check in, find an empty bench, and start typing the day’s notes.”

And then there’s Nabokov’s list of bêtes noires in Pale Fire: “I loathe such things as jazz..abstractist bric-a-brac..music in supermarkets; swimming pools; brutes, bores, class-conscious Philistines, Freud, Marx, fake thinkers, puffed-up poets, frauds, & sharks.”

Totting up our fond loathings is another way of bringing ourselves into sharp focus. In American society, where the prohibition—at least in that tattered remnant of what used to be called polite society—of saying only nice things (or nothing at all) makes for dreary longueurs at the dinner table, we’d do well to remember that we’re not just the sum of our sympathies, but of our enmities, too.

“For a lot of people, their first love is what they’ll always remember,” Christopher Hitchens observed, in a bookchat interview. “For me it’s always been the first hate, and I think that hatred, though it provides often rather junky energy, is a terrific way of getting you out of bed in the morning and keeping you going. If you don’t let it get out of hand, it can be canalized into writing. In this country where people love to be nonjudgmental when they can be, which translates as, on the whole, lenient, there are an awful lot of bubble reputations floating around that one wouldn’t be doing one’s job if one didn’t itch to prick.”

Even for writers who aren’t polemicists eager to pop the overinflated with a well-aimed jab of the nib, lists of things we—or our fictional characters or journalistic or biographical subjects—anathematize can tell the reader volumes about the subject under scrutiny.

In Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, the prep-school drop-out Holden Caulfield’s former teacher Mr. Antolini worries aloud that Holden’s adolescent cynicism (which like so many cynicisms is really just a disillusioned idealism, mugged by life) is going to curdle into bitterness: “It may be the kind where, at the age of thirty, you sit in some bar hating everybody who comes in looking as if he might have played football in college. Then again, you may pick up just enough education to hate people who say, ‘It’s a secret between he and I.’ Or you may end up in some business office, throwing paper clips at the nearest stenographer.” The contempt for football-playing Big-Man-on-Campus conformists, the snobbish disdain for the grammatically hypercorrect prat (and all other species of his archnemesis, the hated “phony”), the impotent fury that expresses itself in petty, ineffectual acts of rebellion: the traits ticked off by Mr. Antolini give us a glimpse of the uglier side of a character who’s had all our sympathies, until now.

(Sei Shônagon, from the series Fashionable Female Six Poetic Immortals (Fûryû onna rokkasen) by Artist: Kikugawa Eizan, 1811. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Public domain.)

The most delicious list of anathemas, to my mind, is the 10th-century Japanese courtier Sei Shōnagon’s “Hateful Things,” from her Pillow Book. (Philip Lopate’s Art of the Personal Essay has a lengthy excerpt accompanied by an insightful, informative introduction.) Shōnagon’s vexations are idiosyncratic in the extreme, and make no apology for it: “I detest anyone who sneezes. … Very hateful is a mouse that scurries all over the place. … Sometimes one greatly dislikes a person for no particular reason—and then that person goes and does something hateful!”

More arsenical bonbons to be savored propped up in bed with a pillow, nightcap within easy reach:

One finds that a hair has got caught in the stone on which one is rubbing one’s inkstick, or again that gravel is lodged in the inkstick, making a nasty, grating sound.

A man who has nothing in particular to recommend him discusses all sorts of subjects at random as though he knew everything. (Mansplaining—in the 10th century!—M.D.)

One is just about to be told some interesting piece of news when a baby starts crying.

A flight of crows circle over with loud caws.

An admirer has come on a clandestine visit, but a dog catches sight of him and starts barking. One feels like killing the beast.

One has been foolish enough to invite a man to spend the night in an unsuitable place—and then he starts snoring.

One has gone to bed and is about to doze off when a mosquito appears, announcing himself in a reedy voice. One can actually feel the wind made by his wings, and, slight though it is, one finds it hateful in the extreme.

The non sequitur raised to the level of a fine art. It’s the sheer apropos-of-nothing nature of “Hateful Things,” coupled with the author’s epigrammatic pithiness and airily imperious sense of the unshakable rightness of her opinions, that gives her lists their gossipy charm and Juvenalian wit.

Epistemologically, lists imply order—categorization, usually; taxonomization, quintessentially. Maybe that’s what makes Shōnagon’s index of her vexations so amusing: its unapologetically miscellaneous nature feels, at times, like a parody of our need to order the world, to have a place for everything and every thing in its place. She calls our foibles and fatuities on the fly as she moves through her days. It’s the cinéma vérité of cynicism.

Lest you think she’s nothing but bitchy, The Pillow Book also includes some exquisitely poetic lists of Adorable Things (“The face of a child drawn on a melon”), Things That Make One’s Heart Beat Faster (“To notice that one’s elegant Chinese mirror has become a little cloudy”), and Things That Arouse a Fond Memory of the Past (“It is a rainy day and one is feeling bored. To pass the time, one starts looking through some old papers. And then one comes across the letters of a man one used to love.”).

Try your own list—of hateful things, favorite things, Whitmanesque passions, talismanic possessions that trace the silhouette of your true self (the books on your shelves, perhaps—a literary shelfie?), Things That Make One’s Heart Beat Faster, or that Arouse a Fond Memory of the Past.

(This post is a revised and expanded version of a series of tweets sent on March 20, 2020.)

A word from our sponsor

Need seasoned editorial help with your lists of Hateful Things, epic catalogues, or whatever-it-is-in-progress? A sounding board for a project that’s still just a gleam in your eye? Coaching to take your writing to the next level? I’d love to help you realize your vision. Visit my editorial and coaching site.

Author: Mark Dery

https://www.markdery.comAs a writing coach, I’m profoundly invested in my clients. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned professional, I can help you take your writing to the next level.

Related Posts