Beware self-consciously clever verbs of attribution. In a widely quoted list of “10 Rules of Writing,” Elmore Leonard thundered against the use of any attributive verb other than “said” and got positively apoplectic at the use of adverbial modifiers (e.g., “he admonished gravely”).

Admired by critics and readers of westerns and crime novels alike, Leonard was known for his wry, knowing dialogue, which updated the choppy syntax and corner-of-the-mouth wisecracks of hardboiled detective fiction for the blown-dry existentialism of ’60s and ’70s America. Writers respected his cool mastery of the American idiom, especially his pitch-perfect ear for dialogue. “I like dialogue,” he told Terry Gross on her NPR show, Fresh Air. “I’ve always liked dialogue from the very beginning. When I started 44 years ago, I was influenced by writers who were very strong in dialogue; Hemingway, John O’Hara, Steinbeck, a writer not many people know about, Richard Bissell in the ’50s. … I like dialogue. I like to see that white space on the page and the exchanges of dialogue, rather than those big heavy, heavy paragraphs full of words. Because I remember feeling intimidated back in the, say, in the ’40s, when I first started to read popular novels, Book of the Month Club books, I would think, god, there are too many words in this book. And I still think there are too many words in most books. But dialogue appeals to me.”

One of the things that makes Leonard’s dialogue snap is his scrupulous avoidance of self-conscious verbs of attribution–verbs that call attention to themselves and in so doing shatter the reader’s illusion that he or she is immersed in the scene, rather than seeing it through the lens of language.

Here’s Rule #3 from his list:

“Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But ‘said’ is far less intrusive than ‘grumbled,’ ‘gasped,’ ‘cautioned,’ ‘lied.’ I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with ‘she asseverated,’ and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

Of course, there are those, like the British novelist Will Self, who refuse to tailor their prose style to the measurements of the mass mind and so have no scruples about sending their readers to the dictionary. But even a writer as fond of sesquipedalian jawbreakers like Self would grant Leonard’s point that verbs of attribution are most effective when they’re invisible.

Leonard forbade the use of adverbial modifiers (“he admonished gravely”) because “they interrupt the rhythm of exchange.” I’ll add that they condescend to the reader by explaining the obvious. If your reader can’t infer the gravity of the admonition, something’s wrong.

As a writing coach, I encourage my clients to consider using “said” at the beginning of a two-person dialogue to clarify who’s who, then, if the exchange is a relatively brief one, to drop the verb of attribution altogether. In well-written dialogue, tone and P.O.V. will make the identity of the speaker clear. If the dialogue rattles on for more than a page and, on re-reading it, you find it difficult to keep track of who’s speaking, so will your reader, and it’s time to insert–as artfully as possible–a reminder.

I had to wean one client from attributions like “She asked,” “He told me,” “She replied,” and the common tic, “I thought to myself.” Much of this literary white noise can be eliminated with the judicious application of a little common sense. For example, doesn’t the question mark tell us that she’s asking a question? Likewise, if he’s telling, that, too, is obvious; ditto replying. And to whom do we think but ourselves (unless we’re telepathic)?

Matt Hart, a freelance journalist who blogs at MattHart.com, notes some amusing precursors to Leonard’s edict, among them an arch admonition to New Yorker editors-in-training from the magazine’s humor writer, Wolcott Gibbs: “The word ‘said’ is O.K. Efforts to avoid repetition by inserting ‘grunted,’ ‘snorted,’ etc., are waste motion, and offend the pure in heart.” Hart cites, as well, this snarky directive from Strunk & White’s deathless Elements of Style:

Do not explain too much.

It is seldom advisable to tell all. Be sparing, for instance, in the use of adverbs after “he said,” “she replied,” and the like: “he said consolingly”; “she replied grumblingly.” Let the conversation itself disclose the speaker’s manner or condition. Dialogue heavily weighted with adverbs after the attributive verb is cluttery and annoying. Inexperienced writers not only overwork their adverbs but load their attributes with explanatory verbs: “he consoled,” “she congratulated.” They do this, apparently, in the belief that the word said is always in need of support, or because they have been told to do it by experts in the art of bad writing.

The trouble with “Rules for Writers,” of course, is that they tend to fossilize into holy writ, especially if the author of the commandments is both a bestseller machine and well-loved by other masters of the craft, as Leonard was. Few rules in the art and craft of writing are inviolable (to use a word that might send the man himself to the dictionary), and Leonard’s are no exception. A steady diet of saids is pretty dreary fare; man does not live by said alone.

(The British humorist John Mortimer, author of the beloved Rumpole novels, has a neat trick for avoiding an endless procession of saids. Before responding to another character, his narrator, the stogie-smoking, Wordworth-quoting, perpetually unkempt barrister Horace Rumpole, tells us, “I was thoughtful.” Then, he speaks. The ruminative aside functions as a kind of attribution, since what follows feels as if he’s giving voice to his thoughts. Following his lead, you might say, when it’s time for a verb of attribution, “Jane was doubtful.” Then Jane expresses her doubts. No need for attribution; we know it’s Jane.)

But there’s another problem with Leonard’s thou-shalt-not prohibition on any verb of attribution but “said”: though it has the skip-the-bullshit ring of common sense, it’s the product of a host of assumptions. It presumes a naturalistic prose style that faithfully transcribes the music of the American Language, as Mencken called it, forgetting that some stylists–unnaturalists, let’s call them–strive for a consciously artificial style. Leonard assumes a prose pitched to the vocabulary, literacy, and attitudes of a mass audience whose special pleasure is crime fiction, a genre as constrained by convention as the Petrarchan sonnet; a prose that has internalized the American suspicion of artifice and veneration of Authenticity (hence Hemingway, the wellspring of Leonard’s inspiration) and our open contempt for intellectualism, a distinctly un-American trait because “elitist,” here in the land where, as the eminent American philosopher Andy Warhol put it, “a Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.”

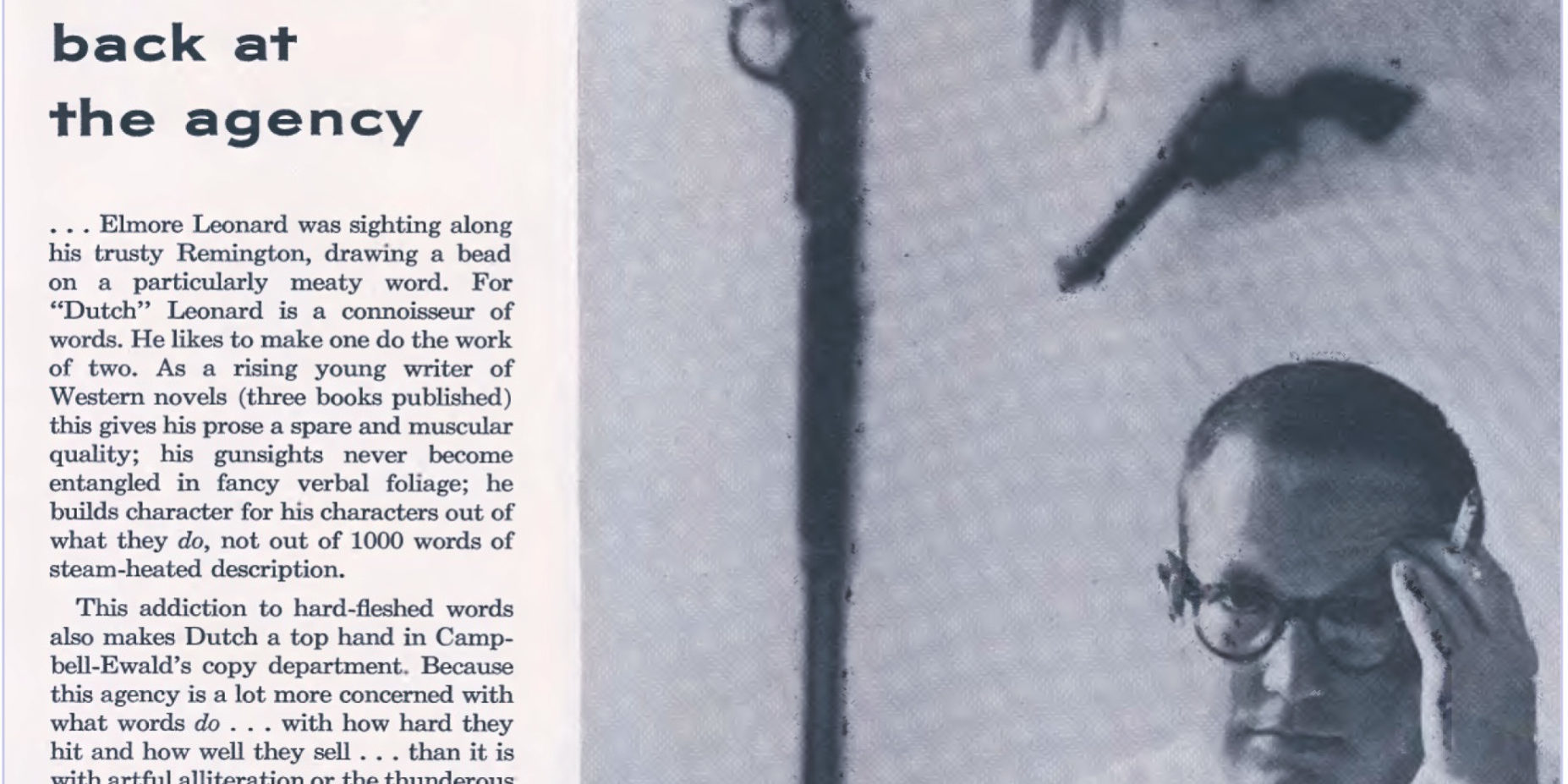

Speaking of which, there’s a PhD thesis to be written about the influence on Leonard’s prose of his time as an ad copywriter, learning to eschew “artful alliteration” and other “fancy verbal foliage.” I mean, if you’re the type who asseverates.

(This article is an expanded version of a series of tweets sent on March 18, 2020.)

Further:

- Elmore Leonard, “How I Write,” GQ, August 20, 2013. “Keep your computer. Give me a Montblanc pen and a pad of paper. The words will follow.”

Author: Mark Dery

https://www.markdery.comAs a writing coach, I’m profoundly invested in my clients. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned professional, I can help you take your writing to the next level.

Related Posts